|

| "Save me, O God, for the waters have come up to my neck." Illustration by Jim Lockey |

$#!+ happens. Everybody hurts. Suffering isn't just a literary ploy utilized in the Psalms for dramatic emphasis--it is the stuff of real life. As humans we endure loss, grief, pain, and uncertainty. Mays points out that these experiences are inherent in the human condition (111). But what else does Psalm 69 teach us is inherent in the human condition?

Because we cannot read a specific historical figure or context out of Psalm 69, it serves as a prayer for many circumstances, circumstances that are as relevant today as they might have been in ancient Israel: alienation from society, friends and family because of one's faith; being falsely accused and accept guilt; feeling isolated and alone in human community. And so, we turn to God. Though Psalm 69 speaks of alienation, it is not speak alienation to us. Instead it speaks of the human ability to reach out to Creator God in times of distress.

We have the capacity for suffering. God has the capacity to hear our laments. But it's more than that. Mays writes, "Nothing that comes to any human being--no tears, no depth, no anguish--is beyond and without the kingdom of God" (Preaching 115). Or, as Paul riffs on Psalm 69, there is nothing that can separate us from the love of God (Rom. 8: 39). The laments also show us that humans have the capacity for praise in the midst of difficulty. It's easy to read the praise turns in the laments and to assume that some major break has occurred in the poem, that some radical change in circumstance has taken place, that God has waved a magic wand to rescue the psalmist from waters that are up to his neck. Rather, I read this shift of praise as another expression of universal and essential humanity--that we can be comforted in the most dire of circumstances by the knowledge of God's sovereign reign. As Mays writes, "We are shown who we are when we pray" (116), and the fundamental message of Psalm 69 is that no matter the circumstances, we are still God's. This affirmation of faith doesn't cure our circumstances, but it does help us to understand that though difficulty may characterize our human condition, these conditions are still embedded in God's steadfast love and abundant mercy (Ps. 69: 16).

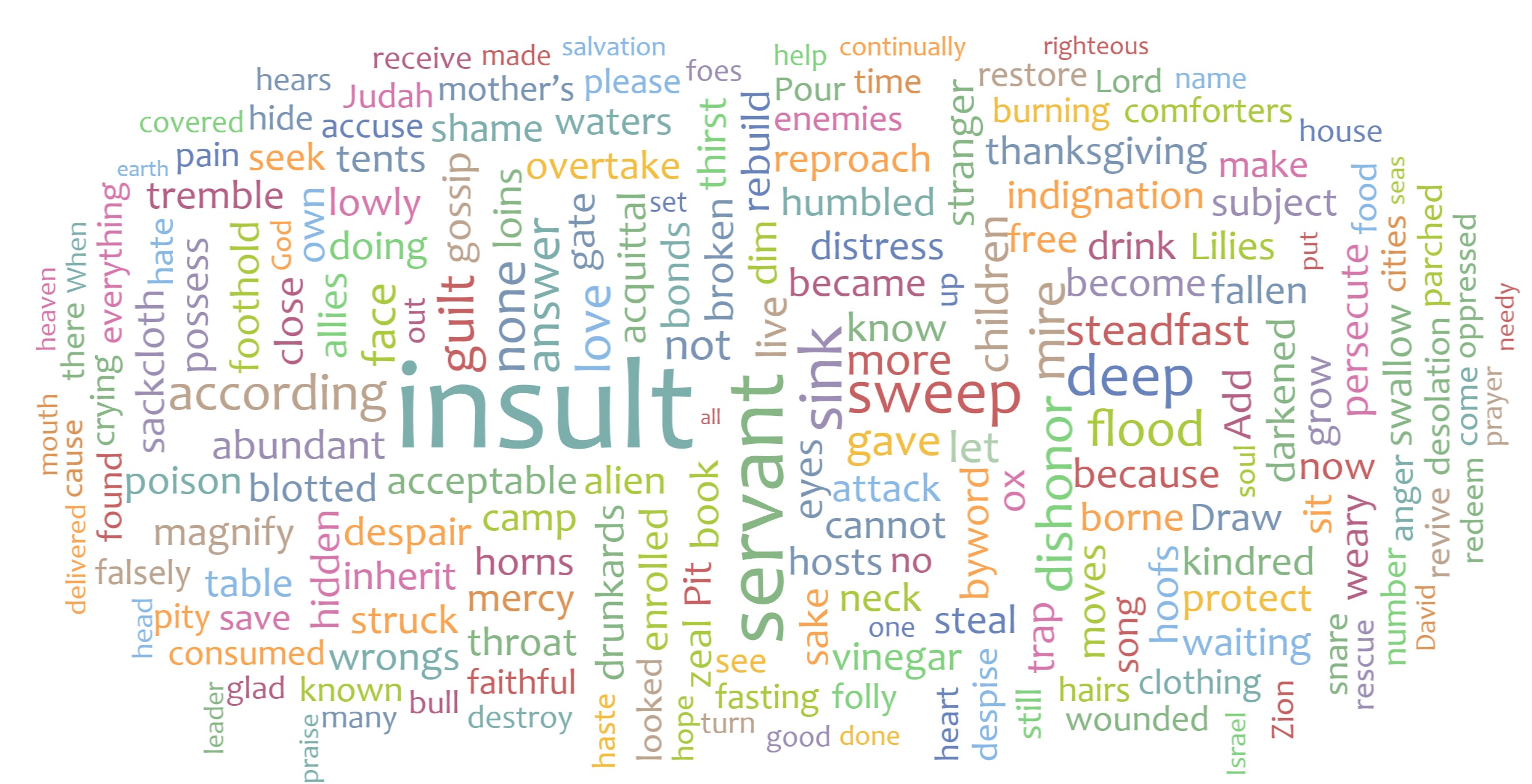

In the first 12 verses of Psalm 69, the psalmist focuses on the situation at hand, looking especially at the wounds inflicted by his fellow human. These experiences are characterized especially by reproach and insult (both Heb. herpa). But when the psalmist turns to examine the character of God in verse 13, it is a different story. In reflecting on the steadfast love and abundant mercy of the Lord, the psalmist cries for a nearness of the Lord--not just to comfort the psalmist, but to enact justice upon the enemies (vss. 22-29). In that turn to praise, the psalmist displays the human capacity to look beyond the present circumstances and to locate a mental space in which it is possible to sing God's praises. McCann characterizes this as an "eschatalogical perspective" (NIB Commentary 953). A movement to praise doesn't mean that everything is perfect. What it means is that the interaction with the divine character has enabled the human to see beyond the present circumstances to the incredible fact that God's graciousness pervades even the moment of crisis. This is good news, indeed.

|

| "Psalm 69: Sinking Not Sunk" by Melani Pyke |

Additionally, I think you'd need to touch on the NT interpretations of Psalm 69 (See Limburg 230), with the understanding that this use of Psalm 69 affirms the deep humanity of Jesus, in that he identified with the suffering and praise present in the psalm, but also acted in an exemplary manner in his faithful relationship with God through that suffering.

No comments:

Post a Comment