UMH: Psalter for Psalm 13, #746

UMH: Be Still My Soul, #534

UMH: Pass Me Not, O Gentle Savior, $351

FWS: How Long, O Lord, #2209

W&S: Falling on My Knees, #3099

W&S: Bidden, Unbidden, 3019

Psalm 13 (How Long O Lord)--Brian Doerksen

Psalm 13--Nate Hale

How Long (feat. Bethany John)--The Psalms Project (Rel. 12/6/2013)

Der 13. Psalm "Herr, wie lange" Op. 27--Johannes Brahms

I Believe--Mark Miller

“I believe in the sun,

even when it is not shining.

I believe in love,

even when I do not feel it.

I believe in God,

even when God is silent.”

This statement of faith was scrawled on a cellar wall in Cologne by a Jewish person hiding from teh Nazi Gestapo during WWII. American soldiers discovered it below a Star of David when searching the bombed house. This poem is the text for Mark Miller's anthem, "I Believe."

Video

How Long from The Inspire Collective on Vimeo.

Depression Conversation Starters:

|

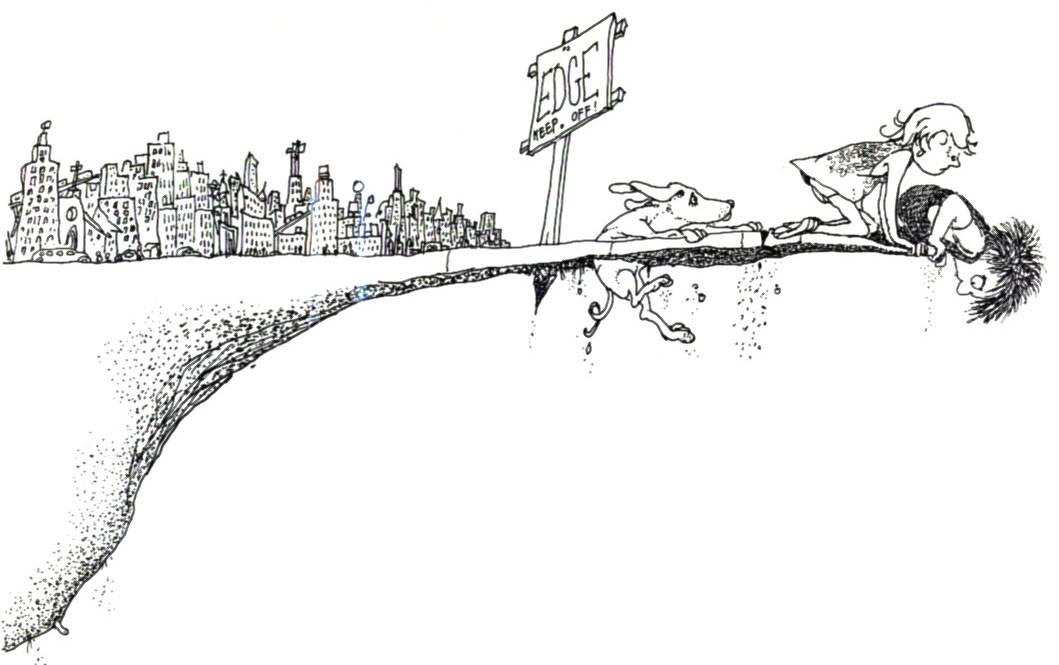

| From "Adventures in Depression, Part Two" Hyperbole and a Half |

Depression Basics -- Halfofus.com